Published: April 2025

Introduction

This paper introduces, for a general audience, the concept of pooled investing through mutual funds and exchange-traded funds or products (ETFs), highlighting why these “basket” products have become essential tools for investors. The paper tracks the major milestones in the evolution of passive investing and describes the key benefits of pooled investment: diversification, increased liquidity of basket constituents, cost efficiency, and accessibility. We wrap up with important opportunities for improvement in ETF markets.

The sections we believe are the most interesting and not broadly discussed are 5.1 and 6.3.

1. Executive Summary

Pooled investing through mutual funds and exchange-traded funds or products (ETFs) provides investors multiple benefits: (i) diversification across a selected category (growth or value; equity or bond; sectors); (ii) increased liquidity for pooled investment and basket constituents; (iii) cost efficiency; and (iv) ease of purchase.

Mutual Funds provide pooled investing but minimal tools for active trading. ETFs are tradable throughout market hours with a redeem/create function performed by market makers to keep ETF value close to NAV. Tools for active trading (futures, margin, and continuous trading) are widely available; the costs to transact and fees are generally lower than mutual funds.

Nonetheless, ETFs have ample room for improvement. In this paper, we sketch out a few, primarily methods such as improving creation/redemption mechanisms and tick size that will save investors and issuers money.

The sections we believe are the most interesting and not broadly discussed are 5.1 and 6.3.

2. Financial Market Fundamentals

Equities, debt instruments, and futures are among the oldest financial tools, forming the backbone of modern markets. Equities (a share of ownership of a company with rights to residual profits and voting on company management) date back to the 1602 initial public offering (IPO) of the Dutch East India Company (Ferguson); debt instruments (interest paying loans and bonds) have existed since ancient Mesopotamia (Green); and futures (agreements for delayed purchase at given prices) trace to medieval European grain markets and 17th-century Japan (Bell et al.). Equities provide ownership while debt provides rights to cash flow and futures hedge the price and cash flows; thus, these instruments underpin today’s global financial system, enabling capital formation and risk management at scale.

Nonetheless, these products may not suitable for the majority of individual investors. Even professional active managers of mutual funds rarely outperform the Standard and Poors (S&P) 500 index. Successfully picking individual equities requires ample understanding of company fundamentals, prospects, management, and exposes investors to market risks (Great Financial Crisis of 2008) and irrational decision making due to fear or greed. Evaluating the trustworthiness of debtors and performance of futures is even more difficult, with even the most sophisticated investors regularly failing to outperform markets. (Kosowski et al.; Griffin et al.)

3. Mutual Funds

The first asset managers observed the above challenges investors faced and realized they could encourage the participation of risk-averse individuals in financial markets and earn fees by offering diversification-as-a-service. Consequently, the first mutual funds were issued in Amsterdam in the 1770s, allowing small investors to pool their assets while wealth managers scaled their roles (i) creating and rebalancing portfolios, (ii) conducting market research, (iii) developing novel strategies. Mutual funds now target all different investor objectives such as growth, income, or sector concentration.

3.1 Closed-End Funds

Although mutual funds generally improved results for investors compared with investing in individual stocks or bonds, these early forms of mutual funds came with challenges. The first pooled-investment vehicles were closed-end mutual funds (CEF), which raise funds through an IPO and issue a fixed number of shares that trade on exchanges; the CEF may raise additional funds by borrowing funds and/or issuing additional shares. Because the share count of CEF funds is generally fixed, the CEF share prices float with supply and demand and routinely deviates from net asset value (NAV). During market turmoil, the discount widens and investors may have difficulty obtaining a reasonable price for their CEF shares. (Lee, Schleifer, and Thaler) Compliance and management fees (including interest charges for leverage) are often much higher than “open-end” mutual funds.

3.2 Open-End Funds

The first “open-end” mutual fund—one able to be redeemed for cash or underlying shares—was created in the United States in 1924. Because the shares are redeemable at NAV, investors must sell their shares during market hours and then receive the NAV at the close of trading. To meet redemptions, mutual fund managers maintain a liquidity buffer, resulting in impaired performance compared with a fully invested portfolio. In addition, many mutual funds used front-end and/or back-end loads to increase their fees and incentivize investors to keep their investments. The compliance and management costs for mutual funds are high as well as the trading costs through brokerages.

Mutual funds allowed more investors to diversify their portfolios. The stock-market crash of 1929 spurred federal oversight; the Investment Company Act of 1940, enforced by the newly formed SEC, codified disclosure rules, leverage limits, and fiduciary duties for all U.S. investment companies. Fueled by a growing middle class saving for retirement, U.S. mutual-fund assets ballooned from about $135 billion in 1980 to roughly $5 trillion by the late 1990s, cementing pooled investing as a cornerstone of personal finance.

Most institutional and individual investors will find the best way to own common stock is through an index fund that charges minimal fees. Those following this path are sure to beat the net results delivered by the great majority of investment professionals.

— Warren Buffett

4. Exchange-Traded Products

Mutual funds, particularly open-end funds, were widely successful, but as described above exhibited high fees and are only redeemable once per day. These two factors limited their use cases to long-term buy-and-hold strategies. To address these two factors and thereby improve tradability, exchange-traded funds or products (ETPs) were developed in the 1990s. State Street developed the first such fund: the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust with the ticker SPY.

The differences between mutual funds and ETFs are summarized below.

| ETFs | Mutual Funds | |

| What are they? | “Baskets of goods” | “Baskets of goods” |

| How are they managed? | Active or Passive | Active or Passive |

| Minimum investment? | Price of one share, must purchase discrete shares thereafter | Usually a minimum investment, but can invest any amount beyond that value |

| Frequency of trading? | Any frequency during exchange hours | Once per day |

| Location of trading? | On-exchange | Through brokerage |

| Management fees? | (Usually) lower | (Usually) higher |

| Other costs? | Exchange fees, regulatory body fees, bid-ask spread, capital gains | Sales/redemption fees, purchasing fees, capital gains |

| Shortable? | Yes | No |

There are more exhaustive discussions of the differences between these two types of products (here, here, and here, for instance) but to understand the benefits (and eventual points of improvement) related to ETFs, we focus on select aspects of their differences.

4.1 ETFs Trade Freely on Exchanges

ETFs are tradable and have continuous liquidity throughout market hours, allowing investors to enter or exit positions at will (and according to market maker quotes). This near-constant liquidity allows for instantaneous responses to news, model changes, rebalancing needs and development of futures products for leveraged investing. Pensions and hedge funds alike invest in ETF-products, not mutual funds.

4.2 ETFs Exhibit Lower Costs Than Mutual Funds

ETFs usually charge lower management fees than mutual funds for several reasons, but the primary one is the Creation/Redemption mechanism. Briefly we will discuss this difference. In a mutual fund, an investor enters a position and then the managers take the investor money and use it to buy securities that make up the fund (underlyings). Since trading must be conducted at NAV in a mutual fund, the time available for a mutual fund to conduct such a purchase is limited, explaining why trading can only occur once per day (e.g. if a NAV is marked at the closing auction, underlying purchases can only be done in the closing auction). The reverse occurs with investors hoping to sell/redeem the fund. The costs of the buy and sell trades, compliance, taxes, and management are all charged to all investors of the fund.

In ETFs, market makers provide liquidity continuously. If there is sufficient investor demand to increase the number of shares outstanding of an ETF, then the market maker will conduct all underlying transactions to seed the additional shares (a creation). The redemption of ETF shares occurs when sufficient investor selling occurs. Market makers frequently can conduct trades at significantly lower costs than mutual funds, saving ETF investors money. Other times, when flows negate each other or are relatively low, they obviate the need to conduct a creation/redemption.

Mutual funds publish their specific fees in their prospectuses and provide historical fee data. ETF investors pay fees in the form of variable bid/ask spreads because ETFs trade on exchanges. To exit a position, an investor needs to hit a bid; to enter, an investor needs to lift an offer. The creation/redemption mechanism keeps these values generally close to NAVs, but transactions may occur away from the theoretical value of the sum of ETF constituents. In some cases, spreads and premia (discounts) from NAV make trading prohibitively expensive. A future article will discuss the mechanisms of ETFs in greater detail.

Suffice to say, ETFs function sufficiently well to allow for both long- and short-term trading. These pooled investment products are so valuable that they have created a multi-trillion dollar global industry, showing marked acceptance and utility. These ETFs hold significant assets under management, make up 10% of market capitalization on US exchanges, and 30% of daily trading volumes (Ben-David et al.). The advent of ETFs has benefited the resulting ecosystem of index providers, issuers, market makers, investors, and extensive intermediary teams. Below, we discuss how ETF trading trends have shaped markets.

4.3 Creation/Redemption

The creation/redemption mechanism helps ensure that an ETF's market price stays close to its net asset value (NAV). Authorized Participants (APs), typically large financial institutions, can create new ETF shares by delivering the underlying assets or redeem shares by exchanging them for those assets. If the ETF is trading above its NAV, APs can buy the underlying assets, create ETF shares, and sell them at the higher market price, profiting from the difference and pushing the price back toward NAV. If the ETF is trading below its NAV, they can buy the ETF shares at a discount, redeem them for the more valuable underlying assets, and sell those, again profiting and nudging the price up. This arbitrage process helps maintain price alignment between the ETF and the value of its holdings. Without it, ETFs could drift significantly from the value of what they actually represent.

In other words, market makers “buy low, sell high” with creations/redemptions representing upper bounds for purchase/lower bounds for sale. Competitive markets push prices towards these levels which are basically NAV plus/minus some fees.

5. ETFs Improve Markets of their Underlying Components

Parsing the impact of ETPs on trading habits in general is a challenging academic exercise. Whether they exacerbate volatility, increase correlation in assets, or improve price discovery is hard to answer (though there are many attempts in the literature [this article cites a few]), but it is clear ETFs are one of the most important innovations in financial markets in recent memory. In this section, we discuss some ways ETFs have shaped markets.

5.1 Corporate Debt

Bonds and other types of debt typically trade in over-the-counter transactions, making them inaccessible to most investors. ETFs led to a paradigm shift in bond market access. As Samara Cohen, Chief Investment Officer of Index Funds at BlackRock, said during the Ondo Summit in 2025, “You can’t have a credible conversation in the bond market without knowing what an ETF is.”

While there are around 4000 distinct stocks, there are millions of bonds. Banks around the world help corporations fund their businesses through debt, with each issuance to each corporation having unique term sheets and underlying risk factors. The breadth of the bond market and the amount of due diligence required to pick winning bonds is difficult even for the most specialized investors, resulting in illiquid markets for individual bonds.

To increase investor access to these important debt instruments, that in turn reduces the cost of capital for corporations (and similarly municipal debt), asset managers have increasingly turned to the ETF market. Beginning in 2002 with iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD), the fixed income ETF market has grown considerably in value and breadth, encouraging greater market sophistication. Total US fixed income ETF assets have doubled in the past five years.

Those historically trading debt instruments benefited from from strong relationships with debt issuers and high degrees of fragmentation. Now, high frequency trading firms are entering the market and dominating the ETF bond market space. As a result, the ecosystem is rapidly changing, with spreads tightening and more entrants flocking to the space. These changes benefit everyone in the debt ecosystem except the old guard who took rents from market inefficiencies, with institutions like ICE, BlackRock, State Street, and others celebrating improved market conditions.

5.2 Bitcoin and Ethereum

Starting January 10, 2024, Bitcoin could be traded on exchange for the first time in an ETP wrapper. Unlike most ETPs, these products don’t exist to allow for passive investing, diversification, or exposure to active management; they are important simply because they allow investors who are restricted to equity investing, or those who do not want to interact directly on-chain, to receive exposure to the exciting opportunities in crypto assets.

When crypto ETPs were listed, markets demonstrated an interesting phenomenon: while crypto fundamentals had not changed in the slightest, the price of Bitcoin soared. Simply creating an ETP product unlocked liquidity, impacting the crypto market similar to the changes seen over years in debt markets. (Shalvardjiev) Ethereum markets demonstrated these dynamics to a lesser extent, but we predict that as ETPs enable investments into new markets such as tokenized RWAs, we will see similar dynamics as pent up demand is able to be released.

6. New Frontiers for ETFs

6.1 Improving Global ETF Access

For the most part, ETFs are only available in their country of origin due to exchange access. In Europe, investors hoping to buy local funds tracking the S&P 500 need to pay higher fees to purchase SPY or IVV. If Europeans buy local S&P 500 ETF shares, they purchase Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) like CSPX LN, but CSPX LN has higher fees than US based counterparts despite functioning practically identically.

Not every market even has access to UCITS or ability to trade funds when exchanges are open, limiting trading. To truly democratize finance by making markets more efficient and by allocating funds to the optimal opportunities, ETFs must be traded 24/7 and globally. Unfortunately, traditional finance rails do not allow for these opportunities.

6.2 Increasing Fractionalization by Lowering Tick Size

In US markets, the smallest price increment an ETF is $0.01. Other markets have similar restrictions. For some funds, this minimum increment can represent a significant cost. If identical funds have a handle of $10 and $100, a one cent price increment represents 10 bps versus 1 bp to cross the spread and enter/exit the position. We discuss how this spread represents a significant cost for investors in our article on BTC (the ETF) trading.

Crypto exchanges support significantly smaller tick sizes, allowing for better pricing and therefore easier trading of funds. While liquid funds now frequently trade “touch/touch” (the bid/ask spread is one cent), we predict funds will not always trade at the smallest pricing increment on-chain, making efficient pricing precision far more important for traders than the current race-to-the-bottom in terms of speed that blocks new entrants from joining markets.

6.3 Reducing ETF Tracking Error

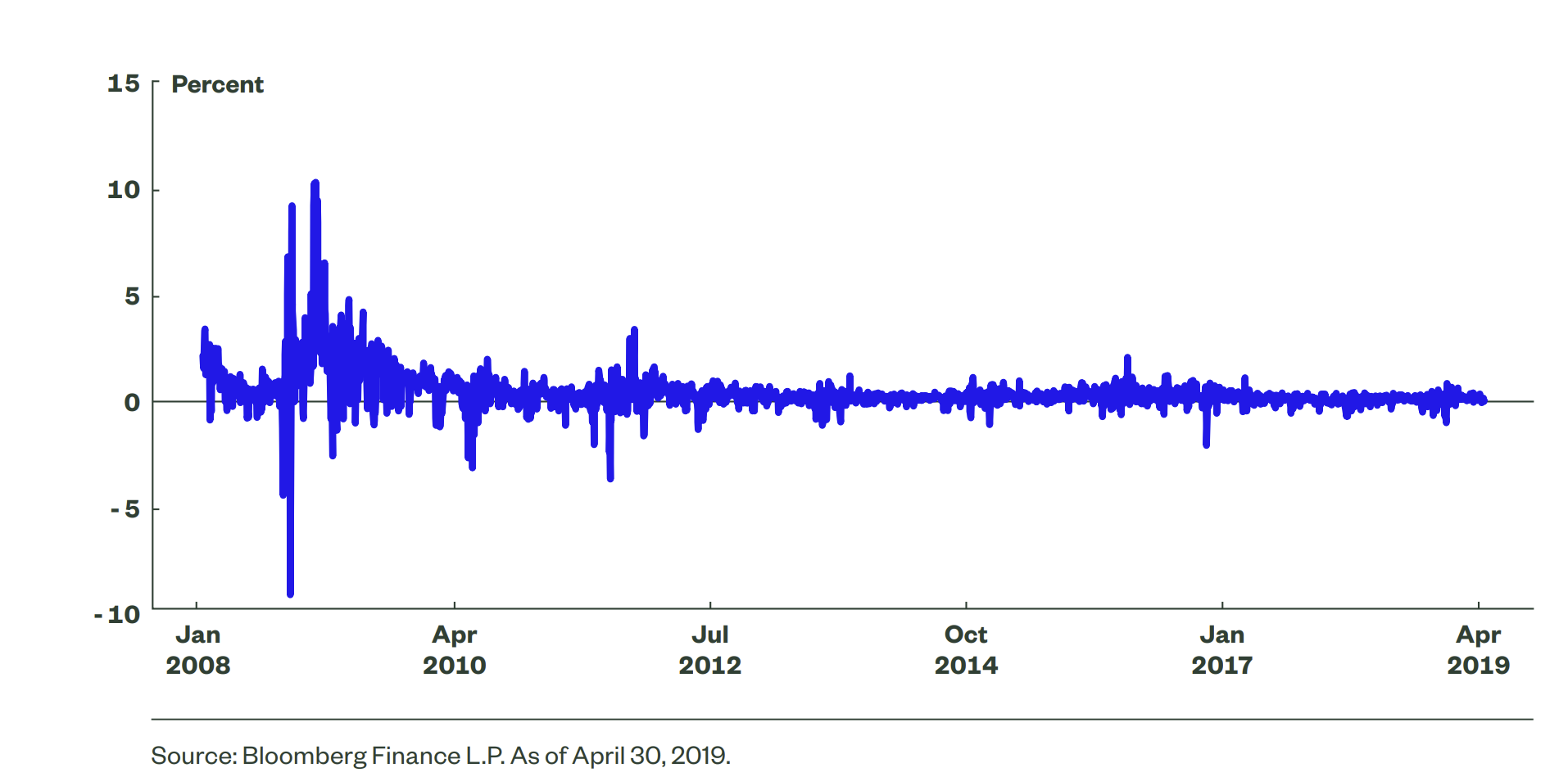

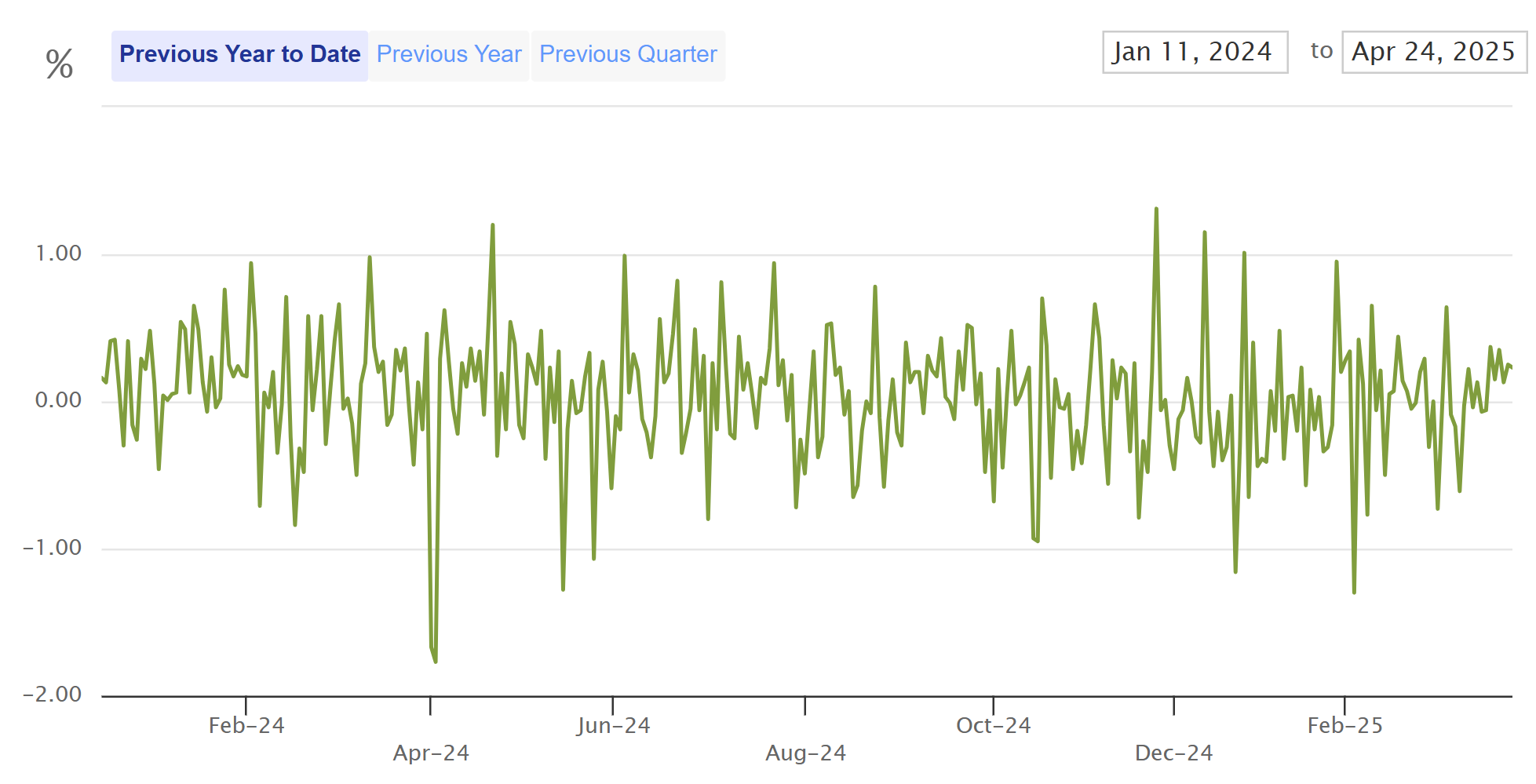

It took over a decade for ETFs in the illiquid bond market to obtain a similar tracking error to that in equity market ETFs. ETFs like JNK (as shown above), have trended over time to a relatively stable range. Some products will never achieve such tight tracking error—even if they have tight spreads and high liquidity—due to structural challenges related to traditional finance markets.

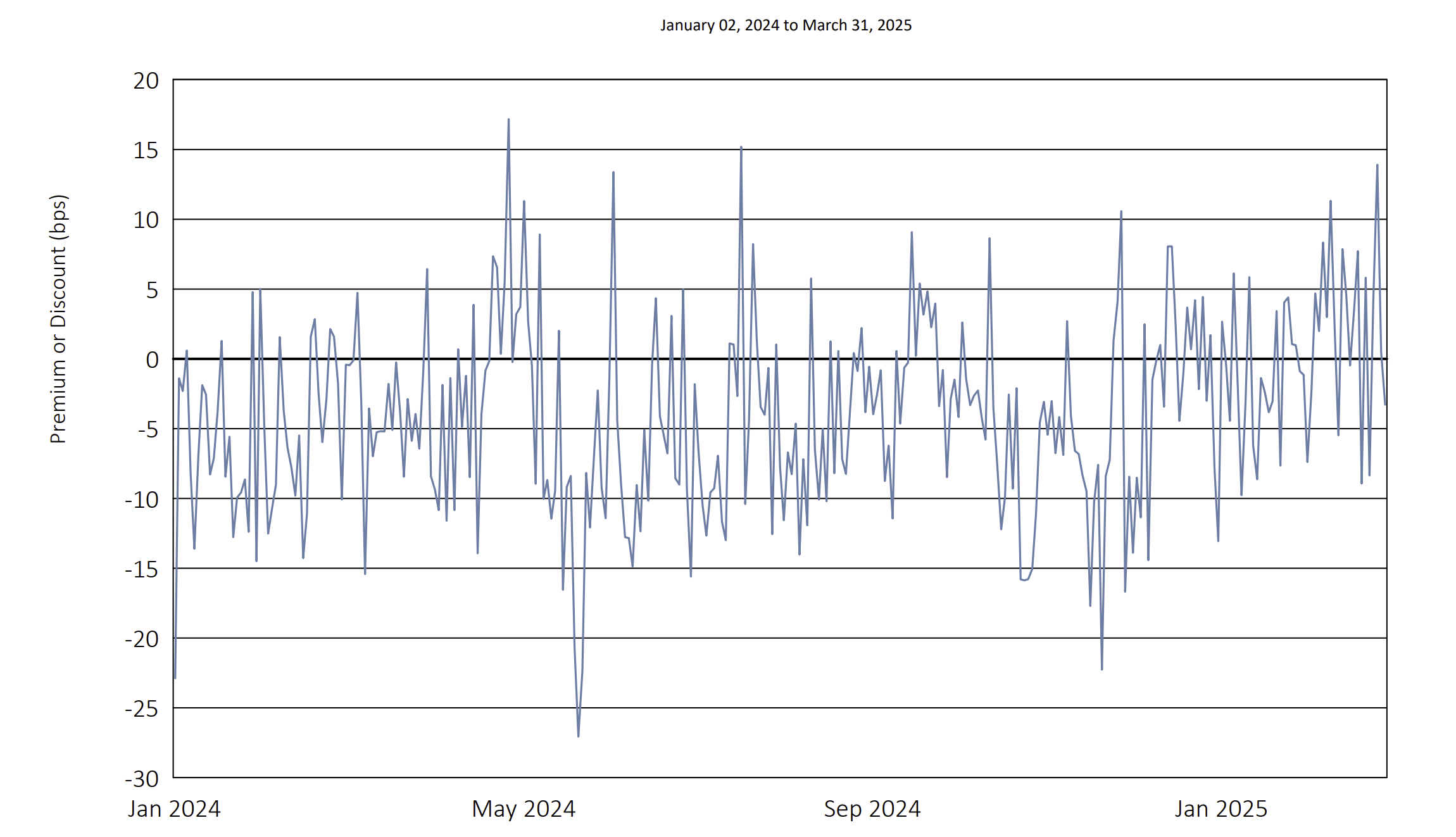

Beyond equities, futures, and debt, some creative issuers have added new products. The rapidly growing space of buffer ETFs, for instance, includes options. For the most part, options are exchange traded, making price replication fairly easy, but many funds hold what are called “flex” options. These options are not exchange traded, meaning that matching their price is very hard, as we see below in the premium/discount chart for one such fund, BMAY.

Other funds hold swaps on indices that are not easy to discern publicly, such as BDRY, which is a pool of swaps on shipping contracts.

Both of these products have generally fine liquidity and trade at penny spreads, but have large swings in premia/discounts reflecting market making costs to enter/exit their position. These swings represent another investor cost in ETPs, as valuation swings can act against positions.

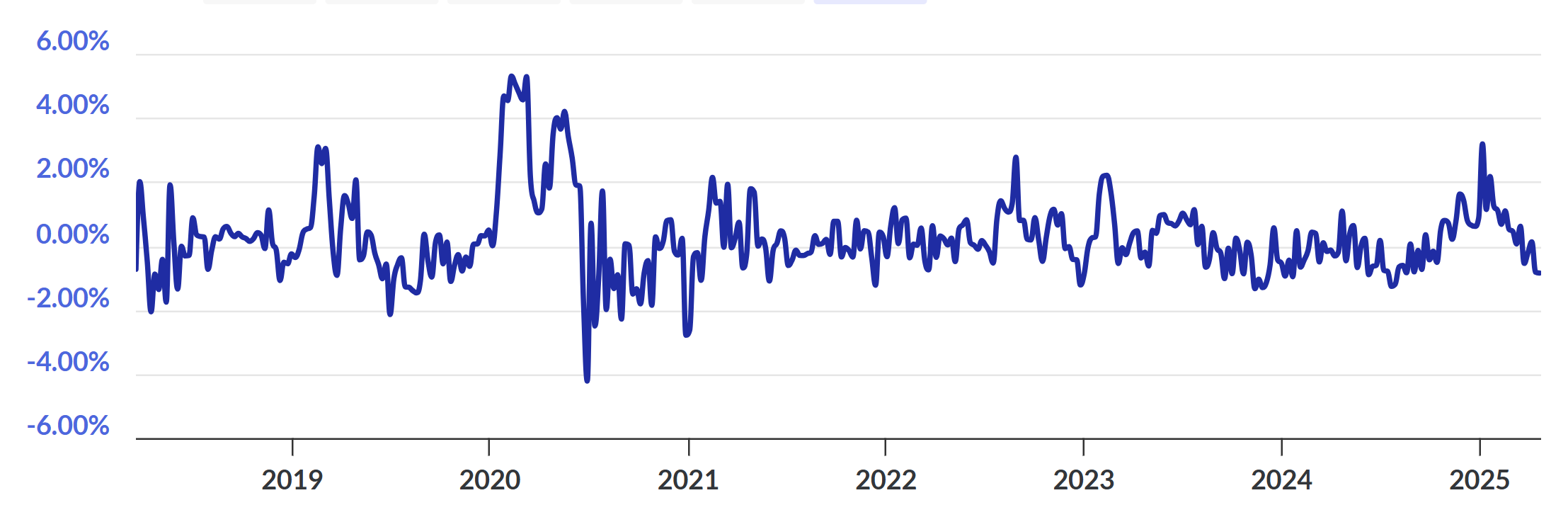

The above funds are relatively complex, but Bitcoin and Ethereum funds are very simple, with orders of magnitude fewer components than SPY and JNK. Even though the underlying components are exchange-traded, these funds trade at significant premia/discounts since an on-chain asset is being wrapped off-chain with associated price uncertainty. Below, we can see the premium/discount chart for USDU (an ETF with thirteen currency underlyings) and IBIT (an ETF with just one currency underlying, Bitcoin).

As we can see from these two graphs, IBIT trades at far greater premia and discounts than USDU, even though it trades at significantly higher volumes. At first, investors might relate these swings to the significant volatility of Bitcoin, but since market makers are hedged, volatility has no impact on premia/discounts (volatility impacts spreads, but IBIT and USDU both trade touch/touch). The true reasoning for this relatively high tracking error is a function of the creation/redemption mechanism. For now, we will suffice to say by improving this mechanism, we can improve the pricing efficiency.

IBIT and other ETFs of its ilk like BITB and ETHA are the most simple possible crypto funds. As more complex funds are developed—such as a CoinDesk 20 ETF (see our paper on the importance of indices)—the divergence from fair value will only increase. In the coming weeks, we will lay out our plans of how we can tighten this gap.

6.4 New Assets

As more assets get tokenized to reduce intermediary costs, we imagine that ETFs will be the tool necessary to help them achieve huge boosts in liquidity as with Bitcoin, Ethereum, and corporate debt. Organizations like BlackRock and Apollo are increasingly adopting blockchain technology to reduce their costs by partnering with organizations like Ondo and Plume to put their assets on chain. To fully utilize these assets and create new markets, we imagine issuers will want to issue ETFs. However, we do not want these products to be overly costly due to challenges for market makers, as with IBIT and BDRY alike. This means that companies like Ondo cannot succeed in improving ETFs by making a tokenized version of SPY, as the difference between TradFi and DeFi rails will lead to high costs. We believe the solution lies on chain, as we will sketch out in future articles.

7. Conclusion

For centuries, financial markets have continually enhanced mechanisms for increased efficient and cost-effective allocations of capital, from fixed income to equity to futures. As markets became more efficient, cost-effective, and with tools for diversification, more people could afford and were willing to become investors. We see this impact of this hurdle through the success of mutual funds and eventually ETPs. However, we posit that pooled investing still has room to evolve, particularly as more assets and ETFs move onto blockchains. Over the coming months, we will expand on this thesis and provide an explanation of our solution.

References

Bell, Adrian, Brooks, Chris, Dryburgh, Paul. Interest rates and efficiency in medieval wool forward contracts. J. Banking & Finance. Vole 31(2), 361.

Ben-David, Itzhak and Franzoni, Francesco A. and Moussawi, Rabih, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) (August 2017). Annual Review of Financial Economics, Volume 9, 2017, Forthcoming, Charles A. Dice Center Working Paper No. 2016-22, Fisher College of Business Working Paper No. 2016-03-022, Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 16-64, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2865734 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2865734

Fergusson, Niall. The Ascent of Money – A Financial History of the World (2009 ed.). London: Penguin. pp. 128–132

Green, Adam. Debt and inequality: Comparing the “means of specification” in the early cities of Mesopotamia and the Indus civilization. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology Vol 60, 101232.

Griffin, John M. and Xu, Jin and Xu, Jin, How Smart are the Smart Guys? A Unique View from Hedge Fund Stock Holdings (March 2007). AFA 2008 New Orleans Meetings Paper, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=924242 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.924242

Kosowski, R., N. Naik, and M. Teo, (2007) “Do Hedge Funds Deliver Alpha? A Bayesian and Bootstrap Analysis,” Journal of Financial Economics 84 (1) pp. 229-264.

Lee, C., A. Shleifer and R. Thaler (1991) “Investor Sentiment and the Closed-End Fund Puzzle,” Journal of Finance 46 (1) pp. 75-109.

Madhavan, Ananth. “Exchange-Traded Funds: An Overview of Institutions, Trading, and Impacts.” Annual Review of Financial Economics, vol. 6, 2014, pp. 311–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44864084. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.

Shalvardjiev, Dimiter, How Bitcoin Etfs Affect Spot Prices. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5115838 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5115838